Jonathan Fildes, BBC

The tangle of cables and plugs needed to recharge today's electronic gadgets could soon be a thing of the past.

US researchers have outlined a relatively simple system that could deliver power to devices such as laptop computers or MP3 players without wires.

US researchers have outlined a relatively simple system that could deliver power to devices such as laptop computers or MP3 players without wires. The concept exploits century-old physics and could work over distances of many metres, the researchers said.

Although the team has not built and tested a system, computer models and mathematics suggest it will work.

"There are so many autonomous devices such as cell phones and laptops that have emerged in the last few years," said Assistant Professor Marin Soljacic from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the researchers behind the work.

"We started thinking, 'it would be really convenient if you didn't have to recharge these things'.

"And because we're physicists we asked, 'what kind of physical phenomenon can we use to do this wireless energy transfer?'."

How wireless energy could work

The answer the team came up with was "resonance", a phenomenon that causes an object to vibrate when energy of a certain frequency is applied.

"When you have two resonant objects of the same frequency they tend to couple very strongly," Professor Soljacic told the BBC News website.

Resonance can be seen in musical instruments for example.

"When you play a tune on one, then another instrument with the same acoustic resonance will pick up that tune, it will visibly vibrate," he said.

Instead of using acoustic vibrations, the team's system exploits the resonance of electromagnetic waves. Electromagnetic radiation includes radio waves, infrared and X-rays.

Typically, systems that use electromagnetic radiation, such as radio antennas, are not suitable for the efficient transfer of energy because they scatter energy in all directions, wasting large amounts of it into free space.

To overcome this problem, the team investigated a special class of "non-radiative" objects with so-called "long-lived resonances".

When energy is applied to these objects it remains bound to them, rather than escaping to space. "Tails" of energy, which can be many metres long, flicker over the surface.

"If you bring another resonant object with the same frequency close enough to these tails then it turns out that the energy can tunnel from one object to another," said Professor Soljacic.

Hence, a simple copper antenna designed to have long-lived resonance could transfer energy to a laptop with its own antenna resonating at the same frequency. The computer would be truly wireless.

Any energy not diverted into a gadget or appliance is simply reabsorbed.

The systems that the team have described would be able to transfer energy over three to five metres.

"This would work in a room let's say but you could adapt it to work in a factory," he said.

"You could also scale it down to the microscopic or nanoscopic world."

Old technology

The team from MIT is not the first group to suggest wireless energy transfer.

Nineteenth-century physicist and engineer Nikola Tesla experimented with long-range wireless energy transfer, but his most ambitious attempt - the 29m high aerial known as Wardenclyffe Tower, in New York - failed when he ran out of money.

Others have worked on highly directional mechanisms of energy transfer such as lasers.

However, these require an uninterrupted line of sight, and are therefore not good for powering objects around the home.

A UK company called Splashpower has also designed wireless recharging pads onto which gadget lovers can directly place their phones and MP3 players to recharge them.

The pads use electromagnetic induction to charge devices, the same process used to charge electric toothbrushes.

One of the co-founders of Splashpower, James Hay, said the MIT work was "clearly at an early stage" but "interesting for the future".

"Consumers desire a simple universal solution that frees them from the hassles of plug-in chargers and adaptors," he said.

"Wireless power technology has the potential to deliver on all of these needs."

However, Mr Hay said that transferring the power was only part of the solution.

"There are a number of other aspects that need to be addressed to ensure efficient conversion of power to a form useful to input to devices."

Professor Soljacic will present the work at the American Institute of Physics Industrial Physics Forum in San Francisco on 14 November.

The work was done in collaboration with his colleagues Aristeidis Karalis and John Joannopoulos.

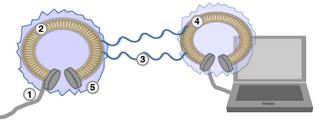

HOW WIRELESS POWER COULD WORK

1] Power from mains to antenna, which is made of copper

2] Antenna resonates at a frequency of 6.4MHz, emitting electromagnetic waves

3] 'Tails' of energy from antenna 'tunnel' up to 5m [16.4ft]

4] Electricity picked up by laptop's antenna, which must also be resonating at 6.4MHz. Energy used to re-charge device

5] Energy not transferred to laptop re-absorbed by source antenna. People/other objects not affected as not resonating at 6.4MHz

No comments:

Post a Comment